‘They didn’t take me seriously’

If the police and social workers had only listened to 12-year-old Ruksana when she told them her father had threatened to send her to Pakistan to be married against her will, then she says life might have been very different.

But they did not take her seriously, she says. She ended up in a foreign country and married to a violent partner who raped her and made her pregnant, aged 15.

Although she managed to escape, Ruksana (not her real name) now lives alone with her young child in a refuge somewhere in England.

Ruksana believes that by taking her away from school so early her parents robbed her of her education. And she says having a child at such a young age has hindered her career.

Let down

“When I was at school. I enjoyed it and worked hard,” she says. “I was in the top sets for English, maths and science. I wanted to go to college and university – but I didn’t even get to take my GCSEs.”

All this may have been prevented, she believes, if she had not been let down by the authorities that she trusted.

With her classmates at school, Ruksana had heard a talk about domestic violence – and some of what she heard chimed with the 12-year-old schoolgirl.

Says Ruksana: “The speaker listed the symptoms and said – if this is happening to you, then it is domestic violence. So I kept his card, and when my parents threatened me with marriage, that’s when I called the police.”

“I told the police: my father wants to send me to Pakistan to get married against my will. I told them that he had my passport.

“The police reassured me that this wouldn’t happen.

Became pregnant

“But then the police came to our house, and talked to me in front of my family – so everyone knew that I had complained. Soon after that the father moved me away to a relative’s house.

“There I was visited by a social worker that the police had arranged. She came to visit me twice – but she also didn’t speak to me alone, so my relatives knew what was going on as well.”

Things moved quickly after that, says Ruksana. “After about six to eight months my father came back from Pakistan. He said: ‘We’re going to Pakistan for a holiday. It’s only for a short time – a month or two’.

“Then when we got on the plane he told me that I wouldn’t be coming back, and that I couldn’t do anything about it.

“After I arrived in Pakistan I stayed there for two years. I got married aged 15 and then got pregnant.

“When I was there I did still secretly think that the British police would come looking for me – because I had already complained to them.

‘Horrific’ experience

“I thought the school in Britain might search for me – I obviously wasn’t coming to school any more. But nobody looked for me. I had to go through all that alone. It was horrific.

“Then I came back to the UK – I did not want to stay married and I told everyone this.

“But they said they had given their word, and if I said no it would bring shame to the family. So I had to go through with it.”

Ruksana gave birth in a British hospital. Then, when her Pakistani husband eventually joined Ruksana in the UK, the marriage was unhappy.

“He was very violent towards me. I have been through rape,” she says.

Eventually Ruksana took her child and ran away. She is now in hiding from relatives who believe she has brought shame on the family name.

“I am always looking over my shoulder,” she says.

She blames the authorities for not believing the word of a 12-year-old Asian girl.

“If they had responded properly then my life wouldn’t be the way it is now,” she says.

“I think maybe the police and social workers aren’t aware of forced marriage Or they think it is an Asian thing and it doesn’t happen with white people.

‘In our tradition’

“White kids can call Childline and they get listened to – but for Asian children it’s thought of as wrong to complain.”

Ruksana is not bitter towards her parents: “I think they know that in our religion – Islam – forced marriage is wrong. But it is also in our tradition.

“From their point of view they were doing the right thing, because that is what happened when they were young.”

And despite her bad experiences, Ruksana would still advise girls in her position to tell the authorities “My message is that they should contact the police and tell them everything.

“Because of the publicity about forced marriages I think they would take you a bit more seriously now.”

|

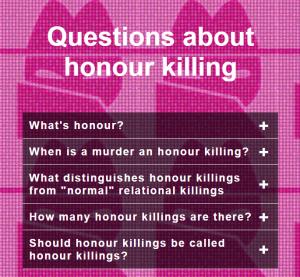

What is an honour killing? |

|

An honour killing is a murder in the name of honour. If a brother murders his sister to restore family honour, it is an honour killing. According to activists, the most common reasons for honour killings are as the victim:

Human rights activists believe that 100,000 honour killings are carried out every year, most of which are not reported to the authorities and some are even deliberately covered up by the authorities themselves, for example because the perpetrators are good friends with local policemen, officials or politicians. Violence against girls and women remains a serious problem in Pakistan, India, Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, Iran, Serbia and Turkey. |

Latest posts

-

Honor Killing in Viry-Châtillon, France: Brothers Beat Their Sister’s Ex-Boyfriend to Death

-

Honor Killing in Ahvaz, Iran: Young woman murdered in front of her husband by her brothers

-

Honor Killing in Abadan, Iran: Daughter Strangled by Her Father

-

Honor Killing in Punjab, Pakistan: Maria Bibi Murdered by Her Father and Brothers

-

Femicide in Mierlo, Netherlands: Syrian woman stabbed to death

-

Domestic Violence Leads to Suicide in Saqez, Iran: Halaleh Eliasi’s Sad Story

-

15-year-old Iranian girl likely murdered because she was in love with a boy

-

Iranian Man Murders 12 As Revenge For Honor Killing Of Sister

-

Honour killing in Dera Ismail Khan, Pakistan: Two brothers murdered their sister

-

Honour Killing in Chennai, India: Young Dalit Stabbed to Death